168 Annual Open - Sharples Gallery Tour by Megan Treacy

We are delighted to say that the RWA is reopening from Saturday 17 April - Sunday 9 May 2021. Book tickets for the 168 Annual Open Exhibition HERE

While we have been closed all artworks have been available for purchase online HERE and you can still do this until 9 May

168 Annual Open Exhibition Tour - Taking Advantage of Chaos

Upon entrance, the Sharples gallery greets us with a versatile array of colour, subject matter, and medium. The variety seemed to provide endless possibilities for the direction of this tour, as even a quick glance at the exhibition space denotes the broad scope of artistic response. Ultimately, I chose five pieces to share in more depth - three paintings, a small sculpture, and a poetry performance - finding in each the theme of taking advantage of chaos. Although some of the pieces were produced before the pandemic, I felt that all of them held relevance to our current way of living and provided optimistic messages in spite of it.

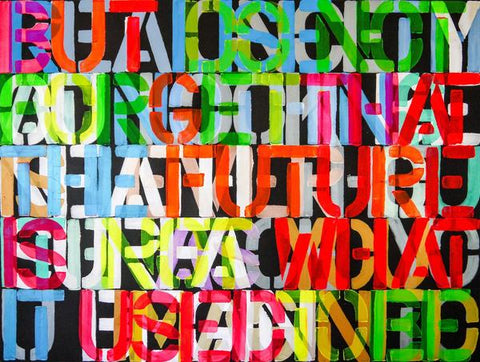

Hanging high on the left wall, Niki Hare’s painting The Future is Not What it Used to Be is one of the first artworks we encounter, demanding attention through its large scale and vibrant colours. Niki used pearly and fluorescent paints which create an illusion of depth in the disembodied letters, as though several messages are trying to force themselves to the forefront. The dominant one reads: ‘But do not forget that the future is not what it used to be’. This message of uncertainty and change is almost self-referential in that the painting is also not what it used to be: the previous stages of the painting are made visible on the canvas through the superimposition of the words, making it a document of its own creation. It seems to evoke the confusion and continuous change of the present time, which makes it interesting that this piece was made in 2019, prior to the pandemic. Speaking of her process, Niki expressed that she liked the way paint ‘behaves, or doesn’t’, relishing ‘the little unintentional things like if you use a stencil that is not quite dry again with another colour you get an edge of the previous colour’. I found optimism in the way the painting deals with unpredictability, the neon colours only shining brighter against the dark background, and despite its initially chaotic appearance, there is a harmony to the way the stencilled letters fit uniformly within the frame, as if suggesting that everything will find the place it’s meant to be.

Further along the wall is another piece which evidences its own evolution in its final form. This is the sculpture entitled Small Step by Andrew Ekins, created with oil on paint skins which are stacked on a shelf, a significantly smaller piece than his other exhibited sculpture, Milk and Honey, in the Winterstoke gallery. Small Step echoes its title in that it appears to be constructed literally of ‘small steps’ which, though inconsiderable on their own, create a larger structure almost like a staircase, the growth of which is visible and satisfying. This is another piece that was produced before the pandemic, yet again it feels significant to our altered everyday life when it can be increasingly difficult to see or incite progress amidst the slowing and halting of the world. I interpreted the sculpture as comforting, a reminder that even when we feel like we are not doing enough, each small action can be seen as part of a bigger effort and attests to the importance of even slight advancements. Andrew uses discarded materials in his work and repurposes them as art, giving unexpected life to things which may seem to have reached dead ends, which is a hopeful idea in a present of cancelled plans and projects. The discarded paint adopts a more substantial role than its intended function, becoming structural rather than simply cosmetic. Additionally, the sculpture’s dripping texture and irregular construction indicates to me that there is room to make imperfect steps towards any goal, as they won’t depreciate the end result.

Towards the end of the wall is the painting Zip Me Up and Cool Me Down by Helen Acklam. If this piece seems to reflect the atmosphere of the pandemic its because it was ‘made in March with all the different emotions and thoughts and turmoil of lockdown’, as quoted from Helen’s Instagram. The form which flashes across the linen surface is reminiscent of lightning, but the image is ambiguous enough that it could even be construed as veins or nerves. In this way, the chaos of the present moment is depicted in both macro and micro terms, conveying our inner relationship to the outer world. The feeling of the pandemic is immortalised here similarly to the way it will be seen in years to come as an intense burst in history, though it feels prolonged while we are living it. Underneath an Instagram post of the painting at an earlier stage, Helen’s caption reads ‘more networks and pathways to nowhere’, describing the way the lightning pattern branches out into the storm of murky purples with no fixed direction, evincing the frustration many are currently feeling. Notwithstanding, I felt that there was a positive light to the piece. Although it is dark and intense it is also beautiful and striking, the disruption of order that it represents is alarming but can also be a catalyst for fresh changes and beginnings when other paths are cut short. As much as lightning shocks and destructs it also illuminates, and chaos may provide opportunities for reflections that may not otherwise have been taken.

On the opposite wall we reach Lauren White’s painting We Have Decided to Be Whole. This title evokes a decisiveness and power which is echoed in the way the girls stare directly out at the viewer. Lauren explained that ‘the painting in general is inspired by a sense of sisterhood and divine femininity’ as well as ‘celebrating a sort of inner goddess’. This is communicated in the subtle imagery of ancient Greek goddesses: a peacock feather for Hera the queen of the gods, flowers across a stomach for Gaia (who embodies the pregnant earth), sunflowers to mark Alectrona the goddess of sunrise, and olives as symbols of the goddess Athena who represents wisdom. The effect of the softly painted image is overwhelmingly warm, and a sense of unity is evoked throughout; the girls are positioned to comfortably lean on and physically support each other and even the flowers and the olives are painted in clusters. The painting was finished in 2019, but it finds relevance now at a time when we are separated from loved ones and support systems. It feels difficult right now to decide to be whole and there is a defiance in this painting against the difficulties of maintaining friendships and human connections. It articulates the perseverance of intimacy and solidarity, and may suggest to us that the time spent apart might be a chance to take control of strengthening and testing relationships.

Circling back to the Sharples gallery entrance, there is a screen playing the video for Josephine Gyasi’s spoken word poetry piece What Are Your Plans? which delivers one of the most crucial and moving messages of the exhibition. Josephine opens her poem with the words ‘I’m sick of death’, referring to the disproportionate amount of murders of Black people by police and racist extremists, adding her voice to the Black Lives Matter movement which was founded in 2013. In a radio interview for SWU FM, Josephine shared that the piece ‘manifested in a very dark place’ after the murder of George Floyd, and that by writing the poem she was ‘asking people to hold themselves accountable and stop being complacent’. She refers to the main addressee in her poem as ‘Mr White Man’ - a personification of the racist and patriarchal structures inherent in society which have caused severe harm to, and often caused the end of, the lives of Black people for so long. The poem questions ‘Why would The White Man change? With no orders from the top?’, acknowledging that the most powerful perpetrators of these structures are unlikely to want change, and so it must be incited by everyday people such as ourselves, the audience of the poem and the people we know. In the accompanying video, Josephine’s hands become stained with red to emphasise the repeated line ‘the blood is on your hands’ which is mouthed by several other Black creatives in a series of close-ups, and the bright red of her tracksuit draws further attention to the violence of the colour. As the video progresses, the “blood” from her hands appears smeared on the wall behind between shots, accumulating unseen just as cases of police brutality and racial violence do day by day, only witnessed in aftermath. Josephine performs the poem using expressive hand gestures, pointing at the camera with purpose to connect us as viewers to her feelings and demand personal responsibility and reflection. The disorder of the pandemic has imposed further obstacles on the Black Lives Matter movement, but the chaos of the time also seems to have urged action in the objective that when life returns to normal, complacency and complicity in racism will not.

To browse all of the 168 Annual Open artworks online click here

Related

Annual Open Exhibitions

About the RWA and the Annual Open Exhibition

168 Annual Open Exhibition

17 April - 9 May 2021

Bristol's Royal Academy presents its 168th Annual Open Exhibition, showcasing some of the most exciting artists from across the country and beyond